Natural hazards and anthropogenic land-use pressures are causing destructive events to occur with increasing frequency, causing severe damage to Archaeological and Cultural Heritage (ACH) sites. As part of the project KulturGutRetter, the Remote Sensing and Monitoring Unit provides cost-effective support based on multi-source satellite datasets for damage assessment and planning on the ground. The studies are categorized into three main approaches: preventive measures, times-series analysis (or monitoring), and rapid response.

Sources and workflows

There are several sources for satellite imagery, such as ESA (European Space Agency), USGS (United States Geological Survey), and NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) which provide their data free of charge. These datasets can be accessed by anyone through their respective data portals. Satellites such as Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 & 9 produce imagery at different spatial, spectral and temporal resolutions. These products can give an overall understanding of the impact, but cannot provide too much detail, as the spatial resolution is limited to 10-15m at best. However, commercial satellites, which can provide spatial resolution down to 30cm, can potentially fill this gap, albeit at substantial cost. The use of freely available datasets should thus be combined with commercial VHR data.

Another goal of our unit is to identify free and easy-to-use analytical toolboxes that will enable archaeologists, cultural heritage and civil protection specialists to work with these datasets. Specifically, we aim to investigate the usability and practicality of remote sensing and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in the case of a crisis and a possible mission of the Cultural Heritage Response Unit (CHRU).

Remote sensing plays a key role in preparing a CHRU mission, to produce maps and plans of the destination area with a strong focus on cultural heritage and archaeological sites. If possible, damages should be mapped remotely, so that the joint team of cultural heritage and civil protection experts has as much information as possible about the situation on-site before going in. This includes information on the cultural heritage sites in the affected area (position, numbers, access roads) as well as visible changes or damage to the sites.

Depending on the nature of the crisis and the local circumstances, there may not be enough time to gather much information on site. Furthermore, it may not be clear how the local infrastructure has been affected and how much useful information could be received via the Internet once the team is at the destination. The same applies to the use of UAVs, which are unlikely to be operational in many cases.

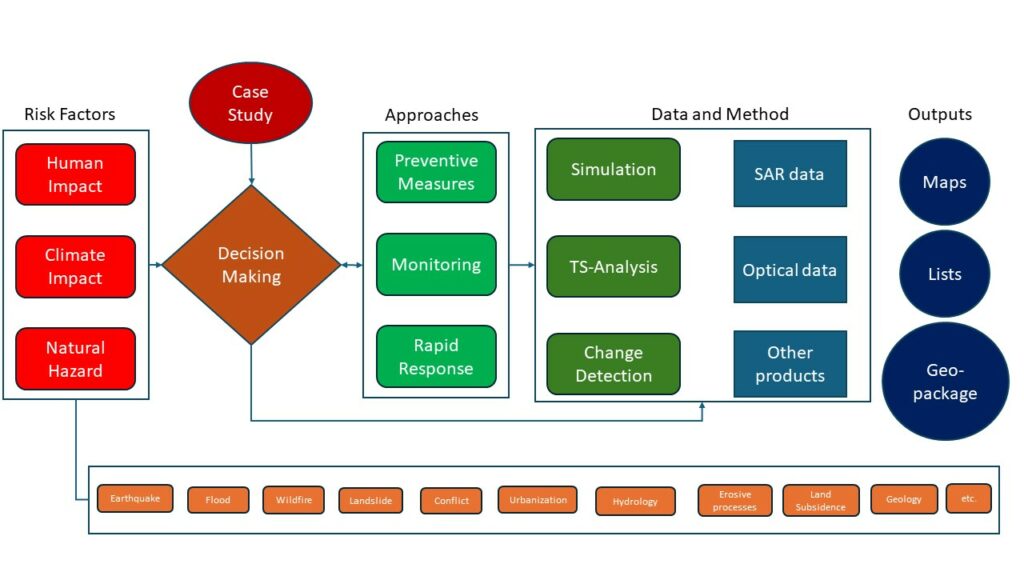

We identified risk factors, approaches and different data and methods that can be used in the case of a new study area (Figure 1) or in an emergency situation. The risk factors are defined based on the source of risk but they are not completely independent of each other and each case study might include more than one factor. After receiving a request regarding an area of interest, depending on the geographical extent of the area and the number of site(s), we explore the potential risks that could be present. We then decide on the best possible approaches, based on the knowledge from different scenarios that we have previously gathered and tested, and start collecting available datasets from different sources. These sources can be either freely available or come from our institutional partners such as the BKG (German Federal Agency for Cartography and Geodesy). We also have a subscription with the proprietary provider Planet Labs, which gives us direct and immediate access to VHR satellite imagery from their SkySat, RapidEye and PlanetScope Dove satellites. In addition, open data programs from various sources such as Maxar can be helpful, especially in case of an emergency.

Figure 1. General workflow of the remote sensing and monitoring unit (SAR stands for Synthetic Aperture Radar and TS-Analysis for Time-Series Analysis) | © Pouria Marzban, DAI

Rapid Response

For each case study, several different types of data and methods are available. For example, in the case of a rapid response, we first look at the activation list of the EU’s Copernicus Emergency Management System (CEMS), to see if they already have analytical products for our area of interest. If not, we start our own data acquisition and procurement processes. It is important to remain flexible in the choice of data processing and analysis methods. Based on post-event data availability and capacity, we decide what type of method to use to detect potentially affected sites. For instance, if we have access to radar data, we can use change detection (damage assessment) methods based on amplitude and phase information; in the case of optical data, we can use feature-based change detection methods. If both types of data are available, combining these methods will lead to more accurate outcomes. This is the advantage of having access to several sources of data and a multi-sensor analysis framework.

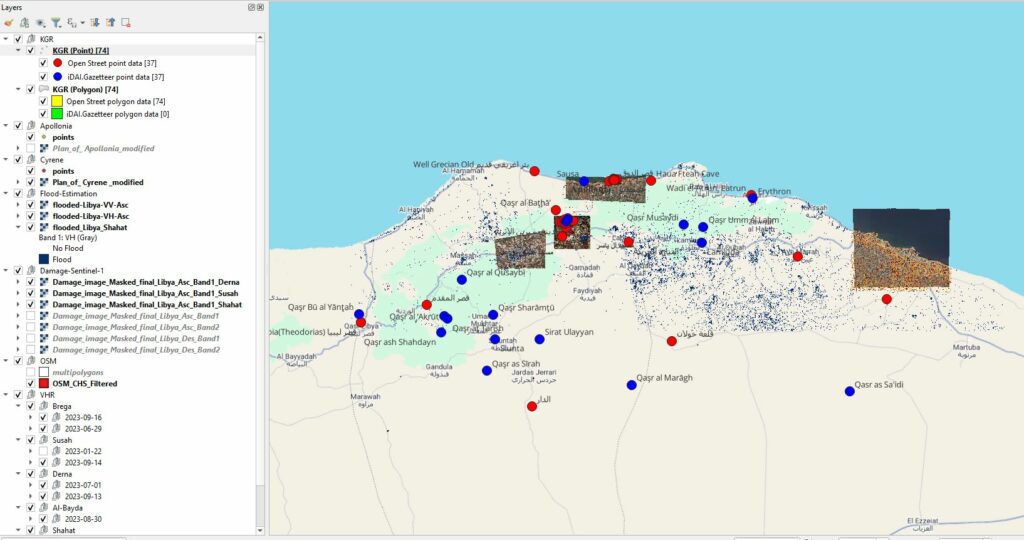

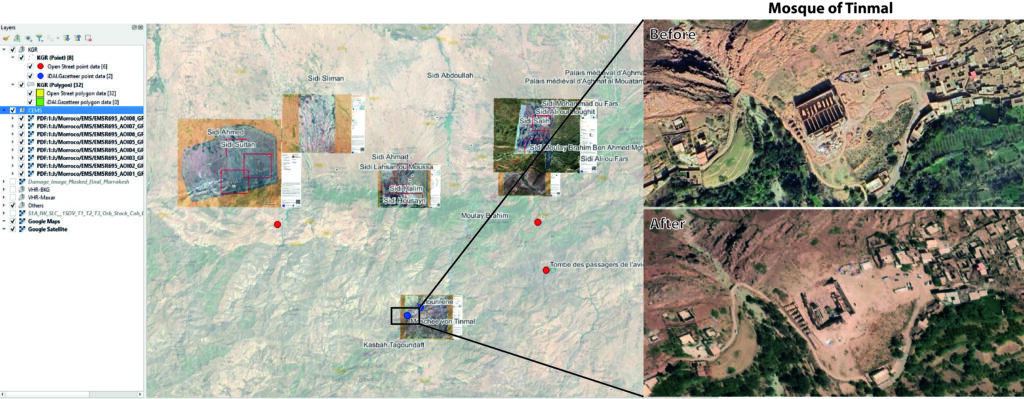

Other sources such as shake maps from the USGS (produced after earthquakes) can be useful in defining our focus areas. GIS sources such as OSM and iDAI.gazetteer (gazetteer.dainst.org) are used to locate cultural heritage sites. We have developed an in-house QGIS plugin called “KGR finder” which can automatically connect to the above sources and download matching archaeological points based on the defined AoI. As examples, we show case studies in Figure 2 where we have combined different analyses.

Figure 2. Example of spatial and remote sensing data on archaeological sites in QGIS. Case of Cyclone Daniel in Libya showing Flood estimation, damage assessment and datasets from different sources (VHR data from Maxar open data and Planets SkySat). |© Pouria

Marzban, DAI

Figure 3. Example of spatial and remote sensing data on archaeological sites in QGIS. Case of Earthquake in Morocco (in this case analysis from CEMS and the VHR data from Maxar open data) | © Pouria

Marzban, DAI

PREVENtIVE MEASURES AND MONITORING

In the case of preventive measures, approaches such as generating hazard maps of a specific area can be carried out using other products from satellite data, such as DEMs (digital elevation models) or land cover/use datasets. For example, DEMs can be used to simulate hydrological or erosion processes and provide information on possible future scenarios. In general, these types of maps and products can be conceptualized based on previous analyses or events.

Long-term monitoring of ACH sites generally focuses on slowly developing phenomena over longer periods, often related to geological movements or climatic changes. For instance, we would use InSAR (Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar) time series analysis to monitor movements such as geological or land subsidence, to look at current and past data and to anticipate future trends. These types of studies can be done with the help of services such as LiCSAR and LiCSBAS or commercial software such as ENVI SARscape or GAMMA. This can also be applied to large areas, on a state or national scale to monitor (for example subsidence) hotspots. For time series analysis of satellite datasets, cloud-based technologies such as GEE (Google Earth Engine) are very popular in the remote sensing community and can be used for ACHS as well. For example, tracking changes over time using the continuous land change monitoring (CCDC) method can help us identify potential hazards over time.

Conclusion

In addition to remote sensing, there are other opportunities and potentially useful data sources for heritage monitoring and damage assessment. These include social media sites and the local network of archaeologists or volunteers who are willing to share information about the situation of ACH sites during or after a crisis situation. To further develop the project and workflow, we are constantly looking for new types of sensors and methods to update our pool of instruments and data. The ultimate goal of our unit is to develop an automated monitoring system for ACH sites worldwide (at least for a selected number of globally representative sites). This will require close collaboration between heritage, civil protection and remote sensing experts. Further collaboration is also needed in the use of newer technological developments such as data science and AI.

Pouria Marzban, Research Assistant – Remote sensing, Benjamin Ducke, Head of IT department, Elvira Iacono, Research Assistant – GIS, Bernhard Fritsch, Data Steward – German Archaeological Institute (DAI) – Scientific Computing Unit, Central Research Services

Extract from the article “Remote Sensing Responses to Hazard and Damage Assessment over Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Sites at Risk”, orginally published in Technical Bulletin #4 from PROCULTHER-NET 2.